TOGETHER

FEBRUARY 1, 2024 - casein, once floating freely, now responds, begins to bond, evolving from fluid state to embryonic curd, all at once, coming together

Content Warning: Text and images in this chapter page refer to death and the traditional rennet-making processes involving young ruminant animals. There is also a brief mention of the ethical complexities of large-scale dairy farming.

SOUR MILK

Last June, I spent five days learning about natural cheesemaking. I tasted a lot of things I hadn’t tried before, nor thought I ever would: warm raw cow’s milk I’d squeezed, raw yak milk from a fellow student who raised them, clabbered milk, and dried, coagulated milk from a young lamb’s stomach.

The class was taught by Trevor, a commercial cheesemaker turned nomadic researcher-educator. He taught us barefoot, outdoors on a raw dairy farm (more firsts). It gave me what every good class should: many more questions than answers and unlikely acquaintanceships.

Sheep, Flock in Owens Valley, Ansel Adams (1941) Public Domain

Sheep, Flock in Owens Valley, Ansel Adams (1941) Public DomainRUMINANTS

Ruminants are plant-eating animals with even-toed hooves, part of the Ruminantia suborder. They digest plant materials by fermenting them in a unique stomach before digestion, mainly through the activity of microbes. Young ruminants have an enzyme in their stomachs called chymosin, which turns their mother's milk into a cheese-like substance. Cheese was likely discovered accidentally; perhaps noticing by storing milk in a pouch made from the abomasum, or the fourth stomach of a ruminant, and noticing it had coagulated. Trevor says milk wants to become cheese.

Before these young animals start digesting grasses, their stomachs are made to digest milk. Their abomasums are harvested at this stage to produce rennet. Though a single abomasum can make a lot of cheese, this fact was what influenced me to research plant-based alternatives. While vegetarian (synthetic) rennets are available on the market, such as the ones that I used in my initial cheesemaking attempts, much of my research involves understanding exactly where my food comes from. These lab-created substances lack any sense of terroir, essentially becoming placeless.

Working with processes that require very few ingredients, like bread and especially aged foods (like cheese or wine), the flavor often comes through fermentation (time + microbial activity) and terroir, that is, the environment in which the ingredients came from. When I’m making cheese with thistle stamens, for example, this environment gets as microscopic as the soil the cardoon was growing in.

Research Poems has been an incredibly worthwhile exploration. However, I realized at Sour Milk School that it also misses an important aspect of the cheesemaking process, the milk, and the animal that milk comes from. Unfortunately, simply using plant-based rennet does not separate me from that process.

When you’re making and eating cheese with homemade rennet from a dehydrated abomasum surrounded by grazing animals, life and death coalesce into a curdled mess. While not slaughtering animals for meat, the dairy industry is not without suffering. That is what happens when living things are treated as individual resources; when what is not useful is discarded.

My seat in class was a white rocking chair. Draped over the top was the hide of the lamb whose stomach we used to make rennet. I am sitting here writing this, still unable to picture that lamb’s tiny curls without feeling deeply upset about it. But I want to sit with it. I might need to sit with this. At least at this scale of a small farm, perhaps I might be able to honor the dead by honoring the living; by making cheese and sharing it with the people I’ve met.

...When making cheese with rennet, you must cut the curd. The coagulation process is incredibly fascinating to watch, a kind of magic or technology. Trevor taught us what he learned through travel, to begin with, the cross: one cut vertically and one horizontally, meeting in the middle where the whey would start to fill the space. It was a gesture of thanks; to the animal whose milk we used, to the other animal whose abomasum, and to each other, for spending time together learning.

When deciding on a final plant for experimentation, I chose sorrel because it was something I could find locally or grow myself. However, like most things, plant rennets are seasonal. I harvested sorrel in the summer, blended my plant material into a juice, and froze it. I knew it would be risky. I knew I probably should’ve just tried then and there. But life gets in the way.

These experiments failed. The milk just didn’t want to coagulate. I have thoughts on why: the freezing, the time of harvest, the cooking temperature, and so on, but I thought it might be good for me to end on something that didn’t work out. It gives me a place to begin. I will grow sorrel in the garden again this year and try once more. Maybe I’ll write about it here too.

These experiments failed. The milk just didn’t want to coagulate. I have thoughts on why: the freezing, the time of harvest, the cooking temperature, and so on, but I thought it might be good for me to end on something that didn’t work out. It gives me a place to begin. I will grow sorrel in the garden again this year and try once more. Maybe I’ll write about it here too.

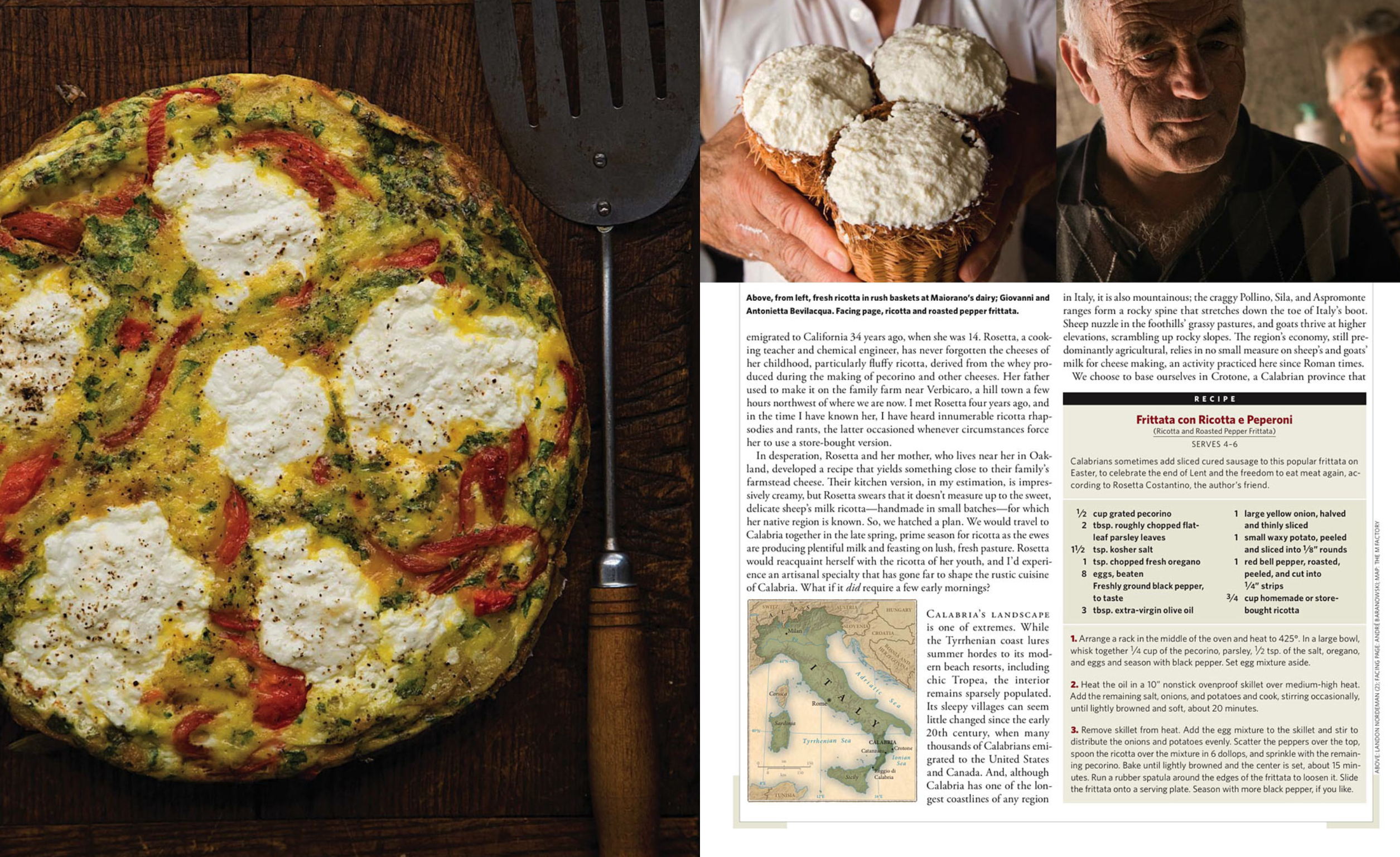

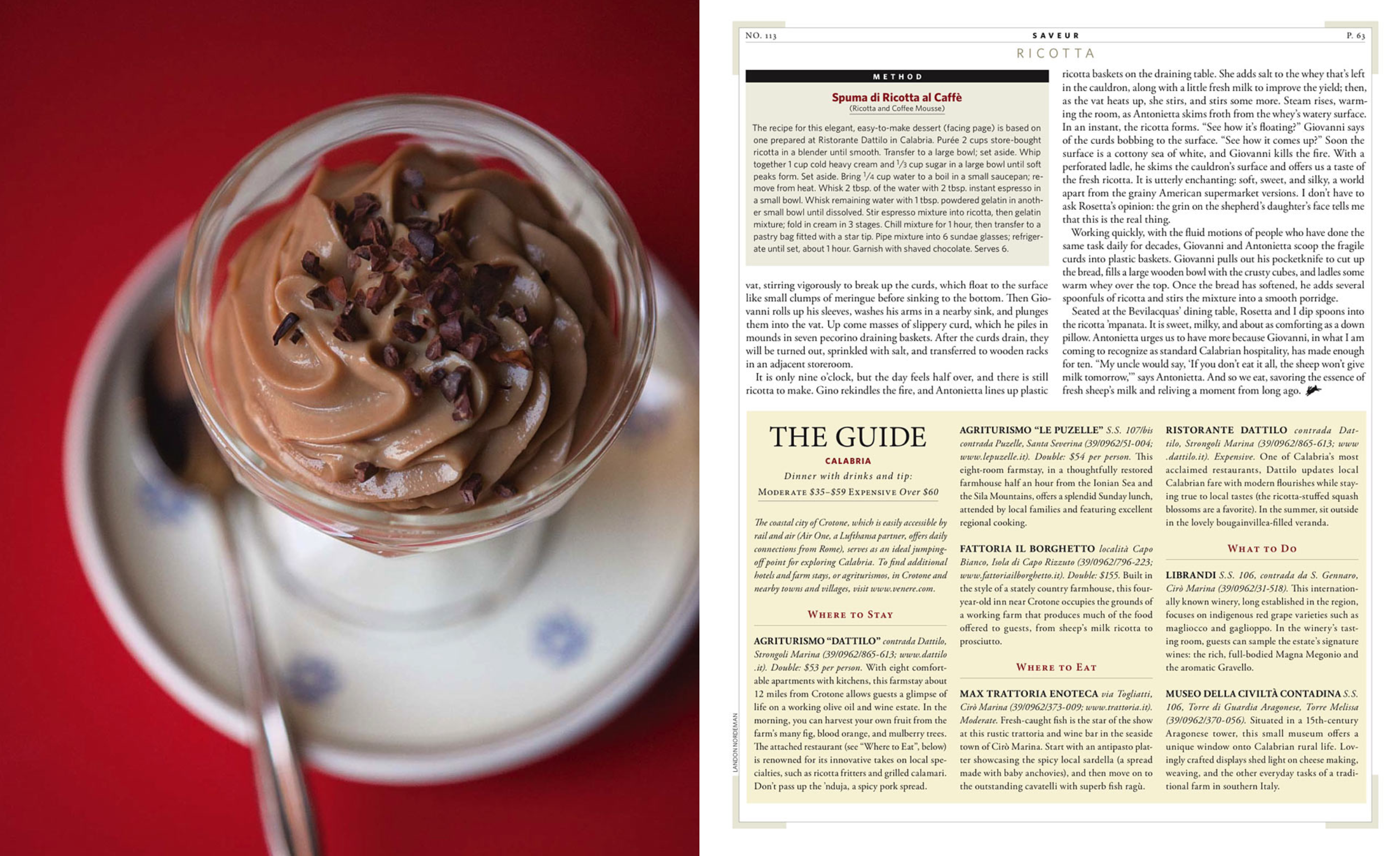

RICOTTA

In place of a new recipe, I wanted to provide you with an old one. Ricotta was the first cheese I made and remains one of my favorites. Made traditionally, it’s a product of reheated, leftover whey. I came across this article in Saveur Magazine about rural Calabrian shepherds and provides a recipe for making ricotta. It’s a fascinating recipe that I’d like to try soon. For now, I have a simpler one (you may already have the ingredients). As I was writing this chapter, I made ricotta again for the first time in a while.

The first recipe I used didn’t turn out how I expected. It yielded some cheese but a small amount and very milky whey. Within simplicity, there are many small ways to make mistakes. There are also several ways to iterate and improve. Unscientifically, my second attempt changed every variable: different milk (fattier + more of it), higher temperature (185° to 200°), different coagulant (lemon to distilled vinegar), and salting (during the heating process instead of after draining).

RECIPE FOR RICOTTA

Ingredients

Add milk to the pot along with salt. Heat your milk on medium heat, stirring often to ensure the bottom layer of milk doesn’t scorch. Once you reach 200°, slowly stream in the vinegar. Continue stirring, gently, and watch as the curds start to separate from the whey. Turn off the heat and let it rest with the lid on for 15-20 minutes.

Ingredients

1/2 gallon (1900ml) whole milk (not ultra-pasteurized)

3/4 cup (180ml) heavy cream

2 1/2 teaspoons (8g) kosher salt

2 1/2 tablespoons (38ml) white distilled vinegar

Method

Add milk to the pot along with salt. Heat your milk on medium heat, stirring often to ensure the bottom layer of milk doesn’t scorch. Once you reach 200°, slowly stream in the vinegar. Continue stirring, gently, and watch as the curds start to separate from the whey. Turn off the heat and let it rest with the lid on for 15-20 minutes.

While you wait, line a colander placed over a bowl with cheesecloth. After 15-20 minutes, scoop the curds into the cheesecloth. (Note: you may want to dampen it slightly to keep it in place.) Then pour the remaining whey and smaller curds. Let the curds drain for anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour. As expected, the longer it drains, the less moisture the cheese will have. Keep the whey to use in baking or cooking, where you might use water, milk, or buttermilk.

This recipe was adapted from here.

![]()

Pasture/cows/life, Rafael Antonio (2015) Public Domain

DISPATCH 04 -

YEAR 21: TENDRIL

Mace sat on the ground, frizzy hair shimmering as the suns set. “Listen,” they whispered. We watched the field of flowers burst open in the golden light. “they’re singing.” “Mhmm," I replied, not quite understanding how a plant could sing. “Close your eyes, and listen,” they said patiently. I stared once more at the Hyzae before us; spindly things.*

I could hear Mace breathing beside me, content and full. I closed my eyes, inhaling a metallic, shimmering sound floating through the air. Soft, hair-like roots burst through the earth, wrapping themselves around my body like tendrils, tugging onto me for support. We sat for ages, holding hands, descending further into the soil. And time kept turning again and again, releasing itself into a star-shaped hole.

*Hyzae flowers have lime petals surrounding a hazel center and small, finger-like, silver leaves. Their petals are quite bitter, but the plant grows well in dry disturbed areas. When the sun split and the earth turned to desert land we acquired the taste for bitterness. Now I have come to crave it.

Pasture/cows/life, Rafael Antonio (2015) Public Domain

DISPATCH 04 -

YEAR 21: TENDRIL

Mace sat on the ground, frizzy hair shimmering as the suns set. “Listen,” they whispered. We watched the field of flowers burst open in the golden light. “they’re singing.” “Mhmm," I replied, not quite understanding how a plant could sing. “Close your eyes, and listen,” they said patiently. I stared once more at the Hyzae before us; spindly things.*

I could hear Mace breathing beside me, content and full. I closed my eyes, inhaling a metallic, shimmering sound floating through the air. Soft, hair-like roots burst through the earth, wrapping themselves around my body like tendrils, tugging onto me for support. We sat for ages, holding hands, descending further into the soil. And time kept turning again and again, releasing itself into a star-shaped hole.

Mace sat on the ground, frizzy hair shimmering as the suns set. “Listen,” they whispered. We watched the field of flowers burst open in the golden light. “they’re singing.” “Mhmm," I replied, not quite understanding how a plant could sing. “Close your eyes, and listen,” they said patiently. I stared once more at the Hyzae before us; spindly things.*

I could hear Mace breathing beside me, content and full. I closed my eyes, inhaling a metallic, shimmering sound floating through the air. Soft, hair-like roots burst through the earth, wrapping themselves around my body like tendrils, tugging onto me for support. We sat for ages, holding hands, descending further into the soil. And time kept turning again and again, releasing itself into a star-shaped hole.